Commentary: Discovering my ancestral ties has deepened my self-identity — a similar journey can help you too

The Genealogy Society of Singapore, a non-profit, recently inked a memorandum of understanding with a China-based ancestry research company to help Singaporeans trace their roots.

The author, Charles Phang, poses for a photo on the steps of his ancestral home in the Taiwanese county of Kinmen.

The Genealogy Society of Singapore, a non-profit, recently inked a memorandum of understanding with a China-based ancestry research company to help Singaporeans trace their roots.

Having just established links with distant relatives overseas, I believe that such initiatives which seek to link individuals with their extended families could benefit Singaporean youth.

I always knew my late grandfather was born in Kinmen, a Taiwanese county situated about 20km off the coast from the Chinese city of Xiamen. But after my eldest uncle passed away three years ago, our family lost all links with our relatives in that part of the world.

So when I made plans to visit Kinmen in September last year to produce a documentary on cross-strait relations, I had no intention of seeking out my extended family.

But when my stringer Jeff mentioned to Hung, a fisherman we were interviewing, that my grandfather was from Kinmen, we soon found that locating my relatives wouldn’t be akin to searching for a needle in a haystack, as I had previously thought.

DOWN GRANDFATHER'S ROAD

When I arrived in Kinmen, I discovered that many people there still reside in traditional Hokkien houses and some live in clusters, according to their family name.

Upon learning my Mandarin surname was “Fang”, Hung directed me to Houtou, a village on a neighbouring island, where if you threw a rock at a random stranger there, you would most probably hit a Fang.

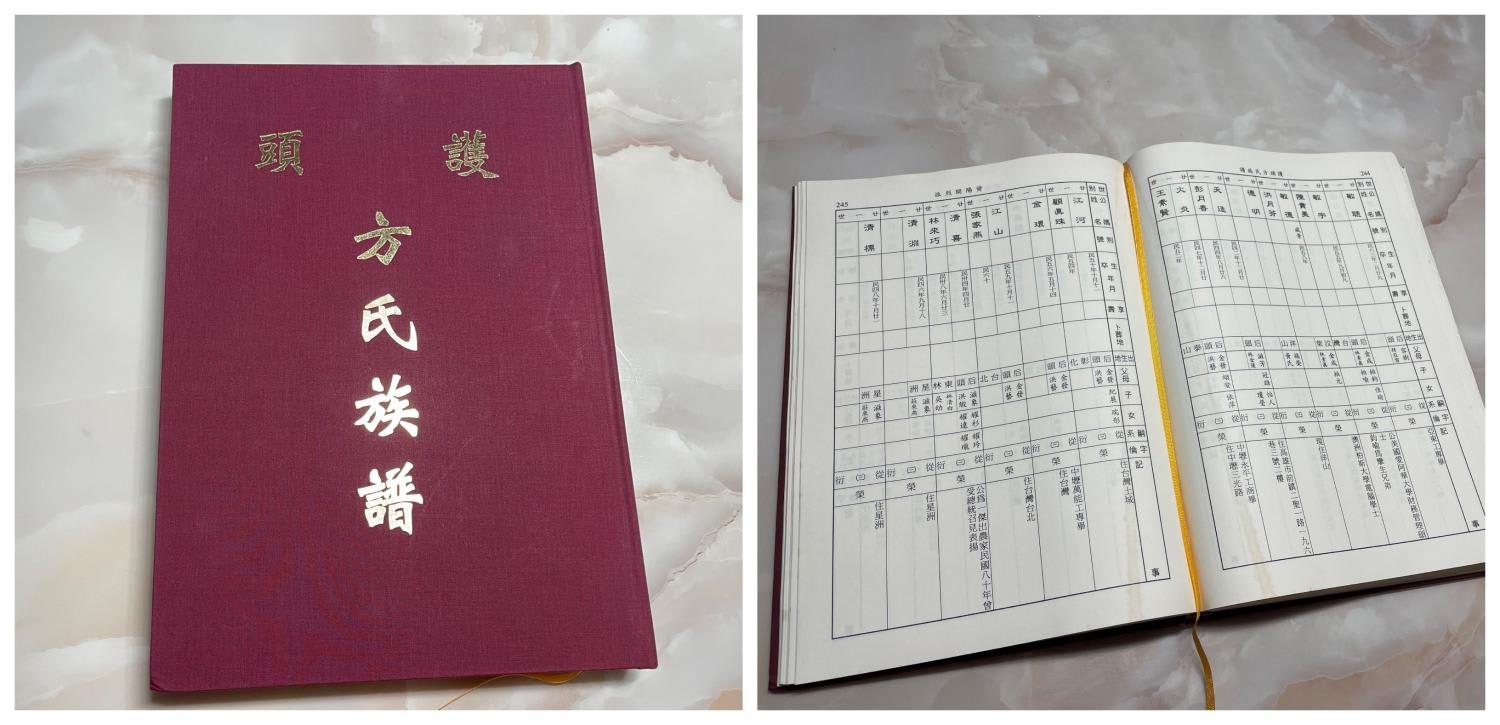

But still, this didn’t mean that I was related to every Fang in town. The key to locating my direct relatives was in my father and grandfather’s Chinese names. Many in Kinmen still adhere strictly to their family’s “Jiapu” or “Family Book”.

The book is passed down through generations.

Among other things, it keeps a record of the family tree and even dictates the middle names of one’s children, grandchildren, and their descendants. These names are traditionally based on a poem chosen by the ancestors.

As both my grandfather and father derived their names from the Family Book, Hung and Jeff were able to identify Houtou residents with the same middle name as my father.

The trail eventually led us to the patriarch of one of the branches of the Fang family, who proved to be a cousin of my grandfather.

He asked me to address him as grand-uncle and took me on a tour of the village, including the ancestral home — a shrine where they honour generations of family members using lanterns, stone carvings and marble plaques.

In just a single visit, I was treated to an overview of nearly 800 years of family history, which went all the way back to China’s Song Dynasty.

I discovered that my family originated from Henan in China, where they lived until the 1200s, when the Mongolian invasion forced my ancestors to travel to Putien in the country’s Fujian province, before eventually settling down in Kinmen.

STRANGER AMONG FAMILY

Despite sharing a surname and 800 years’ worth of history, I initially struggled to connect with my grand-uncle and the host of relatives he invited for dinner to celebrate my “homecoming”.

My grasp of the Hokkien dialect was poor so I relied heavily on Jeff for translation. It was also difficult for me to jump into their conversations because most of the topics were so localised that I had nothing to contribute.

I was also a stranger to many of their customs, including the “sacrosanct” rule that nobody’s allowed to drink alone. To drink from your wine glass, you need to either dedicate a toast to someone at the table, or be toasted to.

However, I managed to discover things that we did have in common.

I learnt that the Singapore-Chinese term for market, “basha” — derived from the Malay word “pasar” — has been widely adopted into the lexicon of the Kinmen community.

This was the result of decades of exchanges between Kinmen residents and people from the Chinese diaspora communities in Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore who maintained links with their hometown.

It’s not just language that binds communities.

A section of my ancestral home in Kinmen is dedicated to celebrating the year and date that a member of the Fang family passed the Chinese imperial exams and was made a magistrate.

This reflects their high regard for meritocracy, which is arguably the closest thing we have in Singapore to a national ideology.

There’s also a stone carving outside the home which depicts a man using his body to shield his father from mosquitoes, which I correctly interpreted as being about filial piety — another value that’s been ingrained in most Singaporeans since childhood.

MORE TO IDENTITY THAN BLOOD

The trip and the discovery of my ancestral ties has given me a lot to reflect on.

First, we shouldn’t discount the role of cultural values in serving as a bridge between diaspora communities and their places of origin.

Recently, there’s been a lot of hype around using DNA technology to determine your ethnicity or to help you locate long-lost relatives.

While tools like these are useful, and scientific developments should be lauded, we should not get too bogged down by the science of it.

You can’t simply expect people located miles away to accept you into their family based on DNA results alone.

Instead, it’s the intangible things like values that will serve as the foundation for fostering a relationship with your extended family overseas.

Identity is determined by more than just blood. You can still embark on a journey to trace your roots without taking a DNA test.

The journey doesn’t necessarily have to end with you locating the exact village your ancestors were from, or finding your actual blood relatives. What’s important is kickstarting that journey using whatever clues that are available to you.

Even if the only information you have is the state or province your ancestors were from — be it Tamil Nadu, Sulawesi or Fujian, it’s still worth making a trip there.

Along the way, pay attention to the little things like the distance your ancestors travelled to get to Singapore, decades ago. Touch and smell the leaves of native plants and most importantly, engage in conversations with locals there.

These are all steps we can take to understand the world our ancestors left behind and establish links with that world.

Next, although the majority of us are descendants of immigrants, our knowledge of our own families’ histories tends to span only two or three generations and is typically limited to the family’s journey in Singapore.

Plugging ourselves into the broader history of our ancestor’s lives in their place of origin also provides us with answers to questions we might have never pondered before.

What were the circumstances that prompted our grandparents or their parents to leave their homes and be part of the mass diaspora to Southeast Asia all those years ago? And why were they willing to venture to a place where there was no guarantee of a roof over their heads?

And what if your ancestors didn’t board that boat to this region and you were born in the same village that they grew up in? What would your life be like today?

The answers to these questions and other insights can add new layers of depth to our personal histories and sense of identity. This will in turn, shape our perspectives of both the present and future.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Charles Phang is a Senior Producer with CNA’s documentary team. He specialises in culture and geopolitics.